In late November, Franklin Learning Center senior Rosario Lemus brought a letter to teachers and administration detailing a list of concerns from student members of the Newcomer Learning Academy (NLA).

Among her requests were respect from cafeteria workers and fellow students, translators that represent more languages spoken by NLA students, and better efforts from the school to administer activities that integrate the NLA into the FLC community.

With 200 students representing 22 languages and 31 countries, the NLA is by far the most international major in an already diverse school. Lemus, along with others in the program, have been building their lives back up from where they were before moving here.

Before coming to the United States, Lemus lived in El Salvador for 16 years. Her family moved here for a better life and future. For the young teen, this city became her refuge and she began attending FLC in 2017. Lemus quickly noticed that during her first years at FLC, students would mock her because of her developing English skills. This took a serious toll on her.

“I didn’t want other people to notice where I am from,” Lemus said. “If I don’t speak English, people will know that I am not from here.”

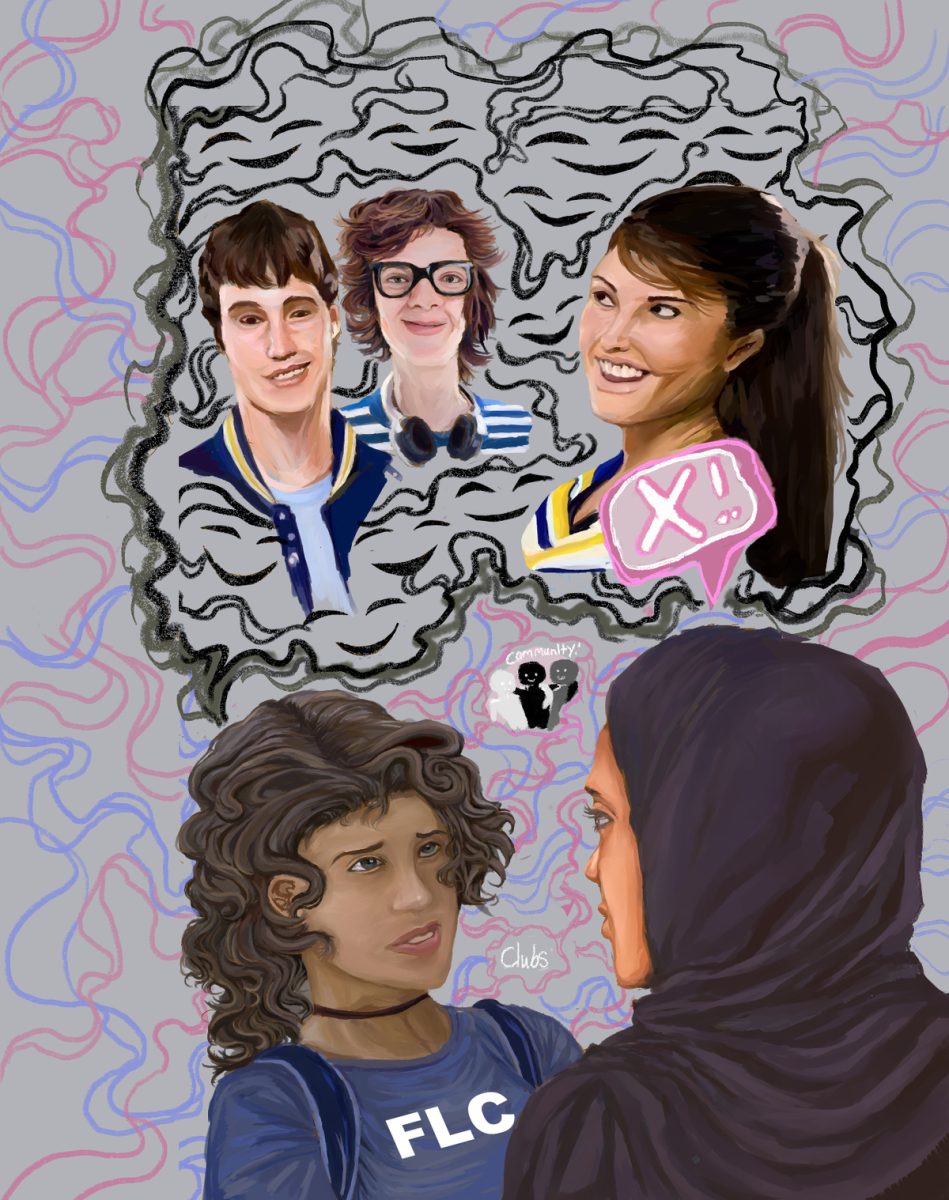

When Lemus started at FLC, she felt good about being in a school that was so diverse. The opportunity to be with the non-NLA students–or, as NLA students call them, the “American kids”–was appealing at first.

“I want my parents to feel proud of me,” Lemus said. “When I came here I didn’t speak English but I want them to think that I’m trying hard for a better future.”

The thrill to start anew and learn English died down as Lemus began to feel unwelcome in the school.

Of the 22 languages spoken by NLA students, Spanish, French, and Haitian Creole are the most common. While all NLA students learn English from ESOL teachers, not all are able to communicate easily with other students in the school. This barrier in communication is one of several reasons NLA students feel isolated and targeted.

These doubts are nothing new when it comes to the NLA students at FLC. Some students in the program feel as though they are a piece of a puzzle not meant for them. This raises the concern that Franklin Learning Center is not doing enough to make NLA students feel comfortable and secure in the school environment.

The Flash FLC approached several students for comment. Many were concerned but ultimately unwilling to share their names publicly. Upon speaking with teachers, we found the students’ concerns are commonly reported to teachers, but solutions are hard to find.

ESOL and English 2 teacher Teresa Higgins says, “Some of [the NLA students] are conscious of the fact they don’t speak English in their approaches for fear that they might be laughed at or misunderstood.”

According to their official website, the NLA aims to “enhance literacy, academic, social and communication skills” and provide “adequate support services including community partnerships, Bilingual Counseling Assistants (BCAs), and counseling support.”

While the School District of Philadelphia claims that this is the program’s focus, NLA teachers agree that the program lacks some resources. The fact that there are very few translators at FLC makes the lives of NLA students and teachers more difficult.

William Mirsky, an ESOL teacher at FLC, agrees that more information in the school should be translated into more languages than just Spanish.

“I know that often times there are things that we translate to Spanish,” he explains, “but there [are] no other language translations.”

Issues with these language barriers often appear during the daily announcements that the school makes. These announcements inform students to look out for tutoring, sports tryouts, school events, and other messages. This information is routinely distributed solely in English. NLA students often can’t understand it and miss out on school updates and the extracurriculars that may help them feel more included in the FLC community.

“Sometimes there’s announcements in Spanish,” Mirsky recalls, “but it’s never in French, or Arabic, or Chinese.”

While it’s definitely a challenge to find translators for all 21 languages in the NLA, the school can begin making announcements in Spanish and French as a start. This way, the NLA students won’t feel as excluded as they do now.

Maynor Lemus Del Cid, an NLA sophomore at FLC, believes that there should be “someone to represent the NLA students” when these announcements are made.

With an NLA representative helping to make announcements, FLC could get more of its students involved in all student activities.

Higgins adds onto this, saying, “[The NLA students] feel left out of school activities…sometimes they just feel [as though] they’re separated in the school in general.”

“There needs to be a lot more collaboration with teachers, there needs to be changes in how rosters are done, especially with new students and what’s available with them.”-Donna Sharer

The School District claims to aid NLA students with social and communication skills, but that becomes difficult when some students are scared to talk. They have few translators to lean on, which stifles potential student advocacy.

NLA teachers have also expressed that with the changes to the curriculum, it’s increasingly becoming harder to teach the NLA about American culture while still maintaining their own.

Donna Sharer, the curriculum development specialist for the NLA at the school district, states, “There needs to be a lot more collaboration with teachers, there needs to be changes in how rosters are done, especially with new students and what’s available with them.”

Other than the changes necessary for the curriculum, teacher preparation for the NLA has been a crucial piece to the puzzle that is missing. Not all the teachers for the NLA can communicate with their students thoroughly due to language barriers, and given the limited resources for translation, this becomes an issue when the students are being taught in class.

While surveying the NLA students, The Flash came across a similar issue. There are 21 languages spoken by the NLA students. To encourage participation, we sent out an anonymous survey to all NLA students with options available in English, French, Spanish, and Arabic. We received responses from 100 students, approximately 50 percent of the program’s population.

In the survey, 55 percent of students indicated that they had been discriminated against by at least one group in the school. 30 percent reported discrimination occurring in the cafeteria.

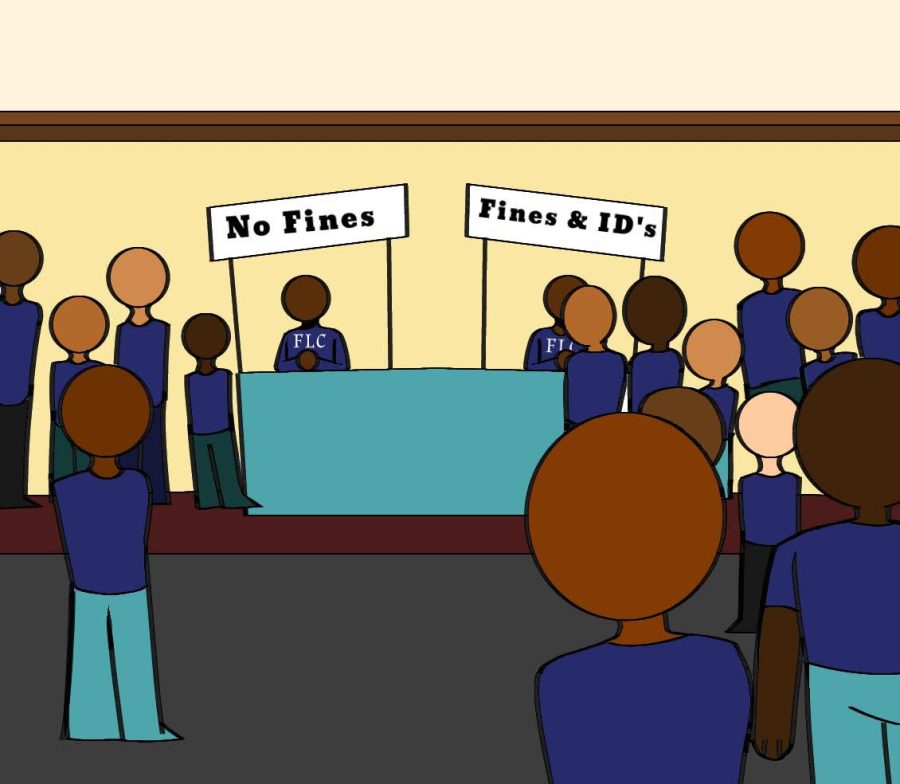

There is an underlying disregard for the well-being of NLA students that is being highlighted at lunch time. NLA students are all grouped together into fourth lunch. On regular days, this lunch period begins at 9:14 AM and on PD schedule (Wednesdays), at 9 AM. On half-days this lunch starts as early as 8:45 AM.

One student, responding in French, said, “Our lunch is very early, it’s more of a breakfast than a lunch. They know that we cannot speak English that’s why they give us the first lunch. In addition, the employees of the cafeteria are very unpleasant.”

Krysten Lopez, another English teacher in the NLA, suggests that “every adult in the building should be exposed to culturally sensitive training. Climate staff, cafeteria workers, janitors, teachers, nurses, administration, [and] bus drivers.”

The Flash reported last year, in a staff editorial, that students from all majors at FLC were avoiding going to the cafeteria. Efforts made to address cafeteria conditions have not solved the problem, at least not for some of the students in the NLA.

In the survey, another student shared their experience with this early lunch period.

The student wrote anonymously, “Fourth lunch made me lose weight and my family was angry I don’t eat any lunch this year.”

In the midst of all of this, there has been hope. Right before the 2019-2020 school year began, FLC was permitted to add in another lunch period. Fourth lunch will no longer be an issue that the NLA must deal with in the next school year.

Roster chair James Arleth recalls, “In August [this year], we finally got approval for a 5th lunch period to deal with the overcrowdedness of only having 4 periods. Since it was so late in the year, we had to move a large group of students’ roster around while having their classes line up as well, and the easiest way to do this in time was with the NLA. This was only to accommodate for this year and we have every intention to balance this out next school year.”

Next to lunch, the school climate is a concern for NLA students.

According to the survey, 22% of responders recalled having changed their own appearance or behavior as a result of discrimination at FLC and 17% said that they have been discriminated against by FLC’s non-NLA students.

Resulting from this prejudice is a change in behavior that the NLA resort to whenever they’re around the non-NLA

“With some of our [NLA students], they tend not to speak,” said Higgins. “It’s the very rare child who is comfortable enough to actually speak out and not worry about how the people are going to watch him or her. We need an opportunity to take away that very soon to be able to interact with each other on a non-judgmental basis.”

As middle school students enter high school, teachers and counselors often plant the phrase “rigorous courses” into their heads. Academic rigor is simply an aspect of education that students will come across in their scholastic journey and it’s a concept that prolongs into college. But for the NLA students at FLC, the chance to explore these intellectual challenges in a classroom setting is limited.

Flexibility in choosing classes does not apply to the students of NLA.

“I believe that they could change the classes,” said senior NLA student Ariel Lopez-Nuñez. “They could put part of the NLA to learn how to speak English and another part where there are only students that speak English”

Everyone at FLC should keep in mind that the NLA students are FLC students before they are NLA. The school should do better and give them a high school experience closest to their ideal high school experience, just as they do for non-NLA students.

Lopez concludes, “NLA students speak another language and have vast levels of different and challenging experiences, but they are still students. They are teenagers like native speaking students. They face similar fears, excitements, identity issues, relationship problems, family issues, [and] stress over the future.”